A Hidden Benefit of HTML5

Try parsing a web page some time. If you’re lucky, it’ll be “correct” HTML without too many typos. You might get away with using some regexes to accomplish this, but be prepared for complex elements and attributes. And good luck dealing with code inside <script> tags.

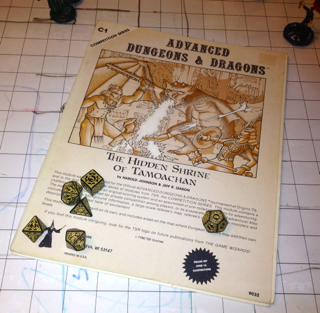

Sometimes there’s a long journey between seeing the potential for HTML injection in a few reflected characters and crafting a successful exploit that bypasses validation filters and evades output encoding. Sometimes it’s necessary to explore the dusty passages of shrines to parsing standards in search of a hidden door that reveals an exploit path.

HTML is messy. The history of HTML even more so. Browsers struggled for two decades with badly written markup, typos, quirks, mis-nested tags, and misguided solutions like XHTML. And they’ve always struggled with sites that are vulnerable to HTML injection.

Every so often, it’s the hackers who struggle with getting an HTML injection attack to work. Here’s a common scenario in which some part of a URL is reflected within the value of an hidden input field. In the following example, note that the quotation mark has not been filtered or encoded.

https://web.site/search?sortOn=x"

<input type="hidden" name="sortOn" value="x"">

If the site doesn’t strip or encode angle brackets, then it’s trivial to craft an exploit. In the next example we’ve even tried to be careful about avoiding dangling brackets by including a <z" sequence to consume it. A <z> tag with an empty attribute is harmless.

https://web.site/search?sortOn=x"><script>alert(9)</script><z"

<input type="hidden" name="sortOn" value="x"><script>alert(9)</script><z"">

Now, let’s make this scenario trickier by forbidding angle brackets. If this were another type of input field, we’d resort to intrinsic events.

<input type="hidden" name="sortOn" value="x"onmouseover=alert(9)//">

Or, taking advantage of new HTML5 events, we’d use the onfocus event to execute the JavaScript rather than wait for a mouseover.

<input type="hidden" name="sortOn" value="x"autofocus/onfocus=alert(9)//">

The catch here is that the hidden input type doesn’t receive those events and therefore won’t trigger the alert. But it’s not yet time to give up. We could work on a theory that changing the input type would enable the field to receive these events.

<input type="hidden" name="sortOn" value="x"type="text"autofocus/onfocus=alert(9)//">

Fortunately, modern browsers won’t fall for this. And we have HTML5 to thank for it. Section 8 of the spec codifies the HTML syntax for all browsers that wish to parse it. From the spec, 8.1.2.3 Attributes:

There must never be two or more attributes on the same start tag whose names are an ASCII case-insensitive match for each other.

Okay, we have a constraint, but no instructions on how to handle this error condition. Without further instructions, it’s not clear how a browser should handle multiple attribute names. Ambiguity leads to security problems – it’s to be avoided at all costs.

From the spec, 8.2.4.35 Attribute name state:

When the user agent leaves the attribute name state (and before emitting the tag token, if appropriate), the complete attribute’s name must be compared to the other attributes on the same token; if there is already an attribute on the token with the exact same name, then this is a parse error and the new attribute must be dropped, along with the value that gets associated with it (if any).

So, we’ll never be able to fool a browser by “casting” the input field to a different type with a subsequent attribute. Well, almost never. Notice the subtle qualifier: subsequent.

(The messy history of HTML continues unabated by the optimism of a version number. The HTML Living Standard defines parsing rules in HTML Living Standard section 12. It remains to be seen how browsers handle the interplay between HTML5 and the Living Standard, and whether they avoid the conflicting implementations that led to quirks of the past.)

Think back to our injection example. Imagine the order of attributes were different for the vulnerable input tag, with the name and value appearing before the type. In this case our “type cast” succeeds because the first type attribute is the one we’ve injected.

<input name="sortOn"

value="x"type="text"autofocus/onfocus=alert(9)//" type="hidden" >

HTML5 design specs only get us so far before they fall under the weight of developer errors. The HTML Syntax rules aren’t a countermeasure for HTML injection. However, the presence of clear (at least compared to previous specs), standard rules shared by all browsers improves security by removing a lot of surprise from browsers’ behaviors.

Unexpected behavior hides many security flaws from careless developers. Dan Geer addresses the challenge of dealing with the unexpected in his working definition of security as “the absence of unmitigatable surprise”.

Look for flaws in modern browsers where this trick works, e.g. maybe a compatibility mode or not using an explicit <!doctype html> weakens the browser’s parsing algorithm. With luck, most of the problems you discover will be implementation errors fixbale within the affected browser rather than a design weakness in the spec.

HTML5 gives us a better design that minimizes parsing-based security problems. It’s up to web developers to give us better sites that maximize the security of our data.