-

I know what you’re thinking.

“Did my regex block six XSS attacks or five?”

You’ve got to ask yourself one question: “Do I feel lucky?”

Well, do ya, punk?

Maybe you read a few HTML injection (aka cross-site scripting) tutorials and think a regex can solve this problem. Let’s revisit that thinking.

Choose an Attack Vector

Many web apps have a search feature. It’s an ideal attack vector because a search box is expected to accept an arbitrary string and then display the search term along with any relevant results. That rendering of the search term – arbitrary content from the user – is a classic HTML injection scenario.

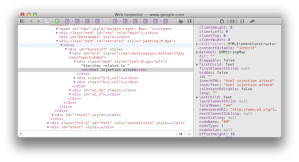

For example, the following screenshot shows how Google reflects the search term “html injection attack” at the bottom of its results page and the HTML source that shows how it creates the text node to display the term.

Here’s another example that shows how Twitter reflects the search term “deadliestwebattacks” in its results page and the text node it creates.

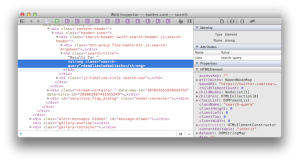

Let’s take a look at another site with a search box. Don’t worry about the text. (It’s a Turkish site. The words are basically “search” and “results”). First, we search for “foo” to check if the site echoes the term into the response’s HTML. Success! It appears in two places: a

titleattribute and a text node.<a title="foo için Arama Sonuçları">Arama Sonuçları : "foo"</a>Next, we probe the page for tell-tale validation and output encoding weaknesses that indicate the potential for a vuln. We’ll try a fake HTML tag,

<foo/>.<a title="<foo/> için Arama Sonuçları">Arama Sonuçları : "<foo/>"</a>The site inserts the tag directly into the response. The

<foo/>tag is meaningless for HTML, but the browser recognizes that it has the correct mark-up for a self-enclosed tag. Looking at the rendered version displayed by the browser confirms this:Arama Sonuçları : ""The

<foo/>term isn’t displayed because the browser interprets it as a tag. It creates a DOM node of<foo>as opposed to placing a literal<foo/>into the text node between<a>and</a>.Inject a Payload

The next step is to find a tag with semantic meaning to the browser. An obvious choice is to try

<script>as a search term since that’s the containing element for JavaScript.<a title="<[removed]> için Arama Sonuçları">Arama Sonuçları : "<[removed]>"</a>The site’s developers seem to be aware of the risk of writing raw

<script>elements into search results. In thetitleattribute, they replaced the angle brackets with HTML entities and replaced “script” with “[removed]”.A persistent hacker would continue to probe the search box with different kinds of payloads. Since it seems impossible to execute JavaScript within a

<script>element, we’ll try JavaScript execution within the context of an element’s event handler.Try Alternate Payloads

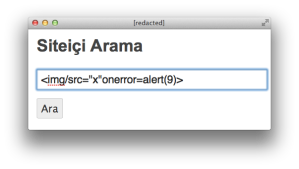

Here’s a payload that uses the onerror attribute of an

<img>element to execute a function:<img src="x" onerror="alert(9)">We inject the new payload and inspect the page’s response. We’ve completely lost the attributes, but the element was preserved:

<a title="<img> için Arama Sonuçları">Arama Sonuçları : "<img>"</a>Let’s tweak the. We condense it to a format that remains valid to the browser and HTML spec. This demonstrates an alternate syntax with the same semantic meaning.

<img/src="x"onerror=alert(9)>

Unfortunately, the site stripped the

onerrorfunction the same way it did for the<script>tag.<a title="<img/src="x"on[removed]=alert(9)>">Arama Sonuçları : "<img/src="x"on[removed]=alert(9)>"</a>Additional testing indicates the site apparently does this for any of the

onfooevent handlers.Refine the Payload

We’re not defeated yet. The fact that the site is looking for malicious content implies that it’s relying on a deny list of regular expressions to block common attacks.

Ah, how I love regexes. I love writing them, optimizing them, and breaking them. Regexes excel at pattern matching and fail miserably at parsing. That’s bad since parsing is fundamental to working with HTML.

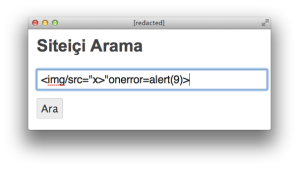

Now, let’s unleash a mighty regex bypass based on a trivial technique – the greater than (>) symbol:

<img/src="x>"onerror=alert(9)>

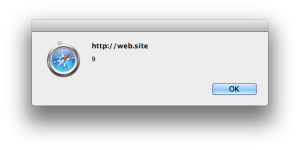

Look how the app handles this. We’ve successfully injected an

<img>tag. The browser parses the element, but it fails to load the image calledx>so it triggers the error handler, which pops up the alert.<a title="<img/src=">"onerror=alert(9)> için Arama Sonuçları">Arama Sonuçları : "<img/src="x>"onerror=alert(9)>"</a>

Why does this happen? I don’t have first-hand knowledge of this specific regex, but I can guess at its intention.

HTML tags start with the

<character, followed by an alpha character, followed by zero or more attributes (with tokenization properties that create things name/value pairs), and close with the>character. It’s likely the regex was only searching foron...handlers within the context of an element, i.e. between the start and end tokens of<and>. A>character inside an attribute value doesn’t close the element.<tag attribute="x>" onevent=code>The browser’s parsing model understood the quoted string was a value token. It correctly handled the state transitions between element start, element name, attribute name, attribute value, and so on. The parser consumed each character and interpreted it based on the context of its current state.

The site’s poorly-chosen regex didn’t create a sophisticated enough state machine to handle the

x>properly. (Regexes have their own internal state machines for pattern matching. I’m referring to the pattern’s implied state machine for HTML.) It looked for a start token, then switched to consuming characters until it found an event handler or encountered an end token – ignoring the possible interim states associated with tokenization based on spaces, attributes, or invalid markup.This was only a small step into the realm of HTML injection. For example, the site reflected the payload on the immediate response to the attack’s request. In other scenarios the site might hold on to the payload and insert it into a different page. That would make it a persistent type of vuln because the attacker does not have to re-inject the payload each time the affected page is viewed.

For example, lots of sites have phrases like, “Welcome back, Mike!”, where they print your first name at the top of each page. If you told the site your name was

<script>alert(9)</script>, then you’d have a persistent HTML injection exploit.Rethink Defense

For developers:

- When user-supplied data is placed in a web page, encode it for the appropriate context. For example, use percent-encoding (e.g.

<becomes%3c) for anhrefattribute; use HTML entities (e.g.<becomes<) for text nodes. - Prefer inclusion lists (match what you want to allow) to exclusion lists (predict what you think should be blocked).

- Work with a consistent character encoding. Unpredictable transcoding between character sets makes it harder to ensure validation filters treat strings correctly.

- Prefer parsing to pattern matching. However, pre-HTML5 parsing has its own pitfalls, such as browsers’ inconsistent handling of whitespace within tag names. HTML5 codified explicit rules for acceptable markup.

- If you use regexes, test them thoroughly. Sometimes a “dumb” regex is better than a “smart” one. In this case, a dumb regex would have just looked for any occurrence of “onerror” and rejected it.

- Prefer to reject invalid input rather than massage it into something valid. This avoids a cuckoo-like attack where a single-pass filter would remove any occurrence of a script tag from a payload like

<scr<script>ipt>, unintentionally creating a<script>tag. - Reject invalid character code points (and unexpected encoding) rather than substitute or strip characters. This prevents attacks like null-byte insertion, e.g. stripping null from

<%00script>after performing the validation check, overlong UTF-8 encoding, e.g.%c0%bcscript%c0%bd, or Unicode encoding (when expecting UTF-8), e.g.%u003cscript%u003e. - Escape metacharacters correctly.

For more examples of payloads that target different HTML contexts or employ different anti-regex techniques, check out the HTML Injection Quick Reference (HIQR). In particular, experiment with different payloads from the “Anti-regex patterns” at the bottom of Table 2.

• • •

• • • - When user-supplied data is placed in a web page, encode it for the appropriate context. For example, use percent-encoding (e.g.

-

Effective security boundaries require conclusive checks (data is or is not valid) with well-defined outcomes (access is or is not granted). Yet the passage between boundaries is fraught with danger. As the twin-faced Roman god Janus watched over doors and gates – areas of transition – so does the twin-faced demon of insecurity, TOCTOU, infiltrate web apps.

This demon’s two faces watch the state of data and resources within an app. They are named:

- Time of check (TOC) – When the data is inspected, such as whether an email address is well formed or text contains a

<script>tag. Data received from the browser is considered “tainted” because a malicious user may have manipulated it. If the data passes a validation function, then the taint may be removed and the data permitted entry deeper into the app. - Time of use (TOU) – When the app performs an operation with the data. For example, inserting it into a SQL statement or web page. Weaknesses occur when the app assumes the data has not changed since it was last checked. Vulns occur when the change relates to a security control.

Boundaries protect web apps from vulns like unauthorized access and arbitrary code execution. They may be enforced by programming patterns like parameterized SQL statements that ensure data can’t corrupt a query’s grammar, or access controls that ensure a user has permission to view data.

We see security boundaries when encountering invalid certs. The browser blocks the request with a dire warning of “bad things” might be happening, then asks the user if they want to continue anyway. (As browser boundaries go, that one’s probably the most visible and least effective.)

Ideally, security checks are robust enough to prevent malicious data from entering the app. But there are subtle problems to avoid in the time between when a resource is checked (TOC) and when the app uses that resource (TOU), specifically duration and transformation.

One way to illustrate a problem in the duration of time between TOC and TOU is in an access control mechanism. User Alice has been granted admin access to a system on Monday. She logs in on Monday and keeps her session active. On Tuesday her access is revoked. But the security check for revoked access only occurs at login time. Since she maintained an active session, her admin rights remain valid.

Another example would be bidding for an item. Alice has a set of tokens with which she can bid. The bidding algorithm requires users to have sufficient tokens before they may bid on an item. In this case, Alice starts off with enough tokens for a bid, but bids with a lower number than her total. The bid is accepted. Then, she bids again with an amount far beyond her total. But the app failed to check the second bid, having already seen that she has more than enough to cover her bid. Or, she could bid the same total on a different item. Now she’s committed more than her total to two different items, which will be problematic if she wins both.

In both cases, state information has changed between the TOC and TOU. The resource was not marked as newly tainted upon each change, which let the app assume the outcome of a previous check remained valid. You might apply a technical solution to the first problem: conduct the privilege check upon each use rather than first use (the privilege checks in the Unix sudo command can be configured as never, always, or first use within a specific duration). You might solve the second problem with a policy solution: punish users who fail to meet bids with fines or account suspension. One of the challenges of state transitions is that the app doesn’t always have omniscient perception.

Transformation of data between the TOC and TOU is another potential security weakness. A famous web-related example was the IIS “overlong UTF-8” vulnerability from 2000 – it was successfully exploited by worms for months after Microsoft released patches.

Web servers must be careful to restrict file access to the web document root. Otherwise, an attacker could use a directory traversal attack to gain unauthorized access to the file system. For example, the IIS vuln was exploited to reach

cmd.exewhen the app’s pages were stored on the same volume as the Windows system32 directory. All the attacker needed to do was submit a URL like:https://iis.site/dir/..%c0%af..%c0%af..%c0%af../winnt/system32/cmd.exe?/c+dir+c:\\Normally, IIS knew enough to limit directory traversals to the document root. However, the %c0%af combination didn’t appear to be a path separator. The security check was unaware of overlong UTF-8 encoding for a forward slash (

/). Thus, IIS received the URL, accepted the path, decoded the characters, then served the resource.Unchecked data transformation also leads to HTML injection vulnerabilities when the app doesn’t normalize data consistently upon input or encode it properly for output. For example, %22 is a perfectly safe encoding for an href value. But if the %22 is decoded and the href’s value created with string concatenation, then it’s a short step to busting the app’s HTML. Normalization needs to be done carefully.

TOCTOU problems are usually discussed in terms of file system race conditions, but there’s no reason to limit the concept to file states. Reading source code can be as difficult as decoding Cocteau Twins lyrics. But you should still review your app for important state changes or data transformations and consider whether security controls are sufficient against attacks like input validation bypass, replay, or repudiation:

- What happens between a security check and a state change?

- How are concurrent read/writes handled for the resource? Is it a “global” resource that any thread, process, or parallel operation might act on?

- How long does the resource live? Is it checked before each use or only on first use?

- When is data considered tainted?

- When is it considered safe?

- When is it normalized?

- When is it encoded?

January was named after the Roman god Janus. As you look ahead to the new year, consider looking back at your code for the boundaries where a TOCTOU demon might be lurking.

• • • - Time of check (TOC) – When the data is inspected, such as whether an email address is well formed or text contains a

-

Friends, Romans, coding devs, lend me your eyes. I’ve created an HTML Injection Quick Reference (HIQR). More details here.

It’s not in iambic pentameter, but there’s a certain rhythm to the placement of quotation marks, less-than signs, and

alertfunctions.For those unfamiliar with HTML injection (or cross-site scripting in the Latin Vulgate), it’s a vuln that can be exploited to modify a web page in a way that changes the DOM or executes arbitrary JavaScript. In the worst cases, the app delivers malicious content to anyone who visits the infected page. Insecure string concatenation is the most common programming error that leads to this flaw.

Imagine an app that allows users to include

<img>tags in comments, perhaps to show off cute pictures of spiders. Thus, the app expects image elements whose src attribute points anywhere on the web. For example:<img src="https://web.site/image.png">If users were limited to nicely formed https links, all would be well in the world. (Sort of, there’d still be an issue of what content that link pointed to, whether obscene, copyrighted, malware, multi-GB images that would DoS browsers or sites they’re sourced from, and so on. But those are threat models for a different day.)

There’s already trouble brewing in the form of javascript: schemes. For example, an attacker could inject arbitrary JavaScript into the page – a dangerous situation considering it would be executing within the page’s Same Origin Policy.

<img src="javascript:alert(9)">Then there’s the trouble with attributes. Even if the site restricted schemes to https: an uncreative hacker could simply add an inline event handler. For example:

<img src="https://&" onerror="alert(9)">Now the attacker has two ways of executing JavaScript in their victim’s browsers – javascript: schemes and event handlers.

There’s more.

Suppose the app writes anything the user submits into the web page. We’ll even imagine that the app’s developers have decided to enforce an https: scheme and the tag may only contain a src value. In an attempt to be more secure, the app writes the user’s src value into an

<img>element with no event handlers. This is where string concatenation rears its ugly, insecure head. For example, the hacker submits the following src attribute:https:">alert(9)The app drops this value into the src attribute and, presto!, a new element appears. Notice the two characters at the end of the line,

">, these were the intended end of the src attribute and<img>tag, which the attacker’s payload subverted:<img src="https:">alert(9)>">A few more tweaks to the payload, such as creating some

<script>tags, and the page is fully compromised.HTML injection attacks become increasingly complex depending on the context of where the payload is rendered, whether characters are affected by validation filters, whether regexes are used to deny malicious payloads, and how payloads are encoded before being placed on the page.

SPQR (Senātus Populusque Rōmānus) was the Latin abbreviation used to refer to the collective citizens of the Roman empire. Read up on HTML injection and you’ll become SPQH (Senātus Populusque Haxxor) soon enough.

• • •

• • •