-

The last few HTML injection articles here demonstrated the ephemeral variant of the attack, where the exploit appears within the immediate response to the request that contained the XSS payload. The exploit disappears once the victim browses away from the affected page. The page remains vulnerable, but the attack must be delivered anew for every subsequent visit.

A persistent HTML injection is usually more insidious. The site still reflects the payload, but not necessarily in the immediate response to the request that delivered it. This decoupling of the point of injection from the point of reflection is much like D&D’s delayed blast fireball – you know something bad is coming, you just don’t know when.

In the persistent case, you have to find the payload in some other area of the app as well as have a means of mapping it back to the injection point. The usual trick is to use a unique identifier for each injection point. This way you know that when you see a page generate a console message with

8675309, it means you can look up the page and parameter where you originally submitted a payload that includedconsole.log(8675309).Typically the payload need only be delivered once because the app persists (stores) it such that any subsequent visit to the reflecting page re-delivers the exploit. This is dangerous when the page has a one-to-many relationship where an attacker infects a page that many users visit.

Persistence comes in many guises and durations. Here’s one that associates the persistence with a cookie.

This paricula app chose to track users for marketing and advertising purposes. There’s little reason to love user tracking (unless 95% of your revenue comes from it), but you might like it a little more if you could use it for HTML injection.

The hack starts off like any other reflected XSS test. Another day, another

alert:https://web.site/page.aspx?om=alert(9)But the response contains nothing interesting. It didn’t reflect any piece of the payload, not even in an HTML encoded or stripped version. And – spoiler alert – not in the following script block:

//<![CDATA[<!--/\* [ads in the cloud] Variables */ s.prop4="quote"; s.events="event2"; s.pageName="quote1"; if(s.products) s.products = s.products.replace(/,$/,''); if(s.events) s.events = s.events.replace(/^,/,''); /****** DO NOT ALTER ANYTHING BELOW THIS LINE ! ******/ var s_code=s.t(); if(s_code)document.write(s_code); //-->//]]>But we’re not at the point of nothing ventured, nothing gained. We’re at the point of nothing reflected, something might still be flawed.

So we poke around at more links. We visit them as any user might without injecting any new payloads, working under the assumption that the payload could have found a persistent lair to curl up in and wait for an unsuspecting victim.

Sure enough we find a reflection in an (apparently) unrelated link. Note that the payload has already been delivered. This request bears no payload:

https://web.site/wacky/archives/2012/cute_animal.aspxYet in the response we find the

alert()nested inside a JavaScript variable where, sadly, it remains innocuous and unexploited. For reasons we don’t care about, a comment warns us not to ALTER ANYTHING BELOW THIS LINE!No need to shout – we’ll alter things above the line.

//<![CDATA[<!--/* [ads in the cloud] Variables */ s.prop17="alert(9)"; s.pageName="ar_2012_cute_animal"; if(s.products) s.products = s.products.replace(/,$/,''); if(s.events) s.events = s.events.replace(/^,/,''); /****** DO NOT ALTER ANYTHING BELOW THIS LINE ! ******/ var s_code=s.t(); if(s_code)document.write(s_code); //-->//]]>There are plenty of fun ways to inject into JavaScript string concatenation. We’ll stick with the most obvious plus (

+) operator. To do this we need to return to the original injection point and alter the payload. (Remember, don’t touch ANYTHING BELOW THIS LINE!).https://web.site/page.aspx?om="%2balert(9)%2b"We head back to the

cute_animal.aspxpage to see how the payload fared. Before we can click to Show Page Source we’re greeted with that happy hacker greeting, the friendlyalert()window.//<![CDATA[<!--/* [ads in the cloud] Variables */ s.prop17=""+alert(9)+""; s.pageName="ar_2012_cute_animal"; if(s.products) s.products = s.products.replace(/,$/,''); if(s.events) s.events = s.events.replace(/^,/,''); /****** DO NOT ALTER ANYTHING BELOW THIS LINE ! ******/ var s_code=s.t(); if(s_code)document.write(s_code); //-->//]]>After experimenting with a few variations on the request to the reflection point (the

cute_animal.aspxpage) we narrow the persistent carrier down to a cookie value. The cookie is a long string of hexadecimal digits whose length and content remain stable between requests. This is a good hint that it’s some sort of UUID that points to a record in a data store where value foromvariable comes from. Delete the cookie and thealertno longer appears.The cause appears to be string concatenation where the

s.prop17variable is assigned a value associated with the cookie. It’s a common, basic, insecure design pattern.So, we have a persistent HTML injection tied to a user-tracking cookie. A mitigating factor in this vuln’s risk is that the impact is limited to individual visitors. It’d be nice if we could recommend getting rid of user tracking as the security solution, but the real issue is applying good software engineering practices when inserting client-side data into HTML.

We’re not done with user tracking yet. There’s this concept called privacy…

But that’s a story for another day.

• • • -

A minor theme in my recent B-Sides SF presentation was the stagnancy of innovation since HTML4 was finalized in December 1999. New programming patterns have emerged since then, only to be hobbled by the outmoded spec. To help recall that era I scoured archive.org for ancient curiosities of the last millennium – like Geocities’ announcement of 2MB (!?) of free hosting space.

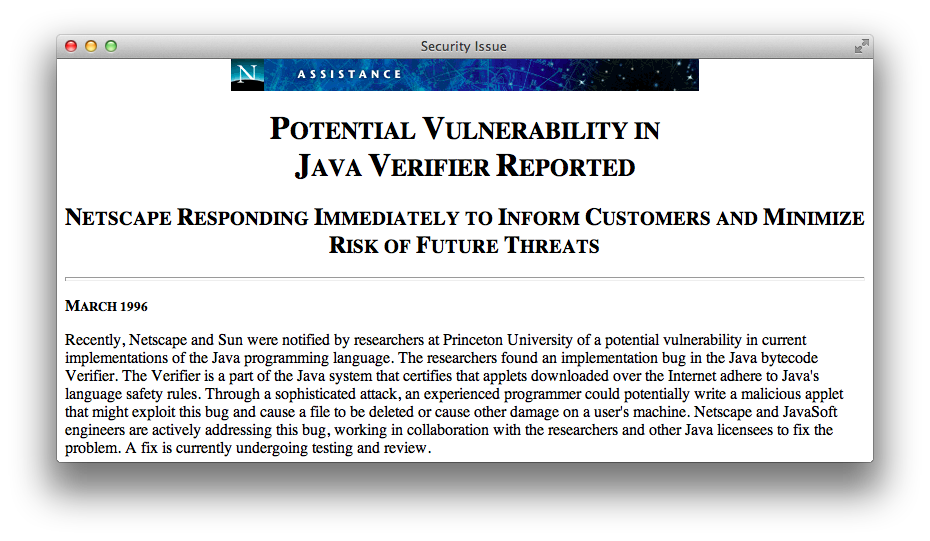

One appsec item I came across was this Netscape advisory regarding a Java bytecode vulnerability – in March 1996.

Almost twenty years later Java still plagues browsers with continuous critical patches released month after month after month, including the original date of this post – March 2013.

Java’s motto

Write once, run anywhere.

Java plugins

Write none, uninstall everywhere.

The primary complaint against browser plugins is not their legacy of security problems, although it’s an exhausting list. Nor is Java the only plugin to pick on. Flash has its own history of releasing nothing but critical updates. The greater issue is that even a secure plugin lives outside the browser’s Same Origin Policy (SOP).

When plugins exist outside the expected security and privacy controls of SOP and the DOM, they weaken the browsing experience. Plugins aren’t completely independent of these controls, their instantiation and usage with regard to the DOM still falls under the purview of SOP. However, the ways that plugins extend a browser’s network and file access are rife with security and privacy pitfalls.

For one example, Flash’s Local Storage Object was easily abused as an “evercookie” because it was unaffected by clearing browser cookies and whether browsers were configured to accept cookies or not. Even the lauded HTML5 Local Storage API could be abused in a similar manner. It’s for reasons like these that we should be as diligent about demanding privacy fixes as much as we demand security fixes.

Unlike Flash, the HTML5 Local Storage API is an open standard created by groups who review and balance the usability, security, and privacy implications of features intended to improve the browsing experience.

Creating a feature like Local Storage and aligning it with similar security controls for cookies and SOP makes them a superior implementation in terms of preserving users’ expectations about browser behavior. Instead of one vendor providing a means to extend a browser, browser vendors (the number of which is admittedly dwindling) are competing to implement a uniform standard.

Sure, HTML5 brings new risks and preserves old vuln in new and interesting ways, but a large responsibility for those weaknesses lies with developers who would misuse an HTML5 feature in the same way they might have misused AJAX in the past.

Maybe we’ll start finding poorly protected passwords in Local Storage objects, or more sophisticated XSS exploits using Web Workers or WebSockets to exfiltrate data from a compromised browser. Security ignorance takes a long time to fix. Even experienced developers are challenged by maintaining the security of complex apps.

HTML5 promises to make plugins largely obsolete. We’ll have markup to handle video, drawing, sound, more events, and more features to create engaging games and apps. Browsers will compete on the implementation and security of these features rather than be crippled by the presence of plugins out of their control.

Getting rid of plugins makes our browsers more secure, but adopting HTML5 doesn’t imply browsers and web sites become secure. There are still vulns that we can’t fix by simple application design choices like including X-Frame-Options or adopting Content Security Policy headers.

Would you click on an unknown link – better yet, scan an inscrutable QR code – with your current browser? Would you still do it with multiple tabs open to your email, bank, and social networking accounts?

You should be able to do so without hesitation. The goal of appsec, browser developers, and app owners should be secure environments that isolate vulns and minimize their impact.

It doesn’t matter if “the network is the computer” or an application lives in the cloud or it’s something as a service. It’s your browser that’s the door to web apps and, when it’s not secure, an open window to your data. Getting rid of plugins is a step towards better security.

• • • -

The article rate here slowed down in February due to my preparation for B-Sides SF and RSA 2013. I even had to give a brief presentation about Hacking Web Apps at my company’s booth. (Followed by a successful book signing. Thank you!)

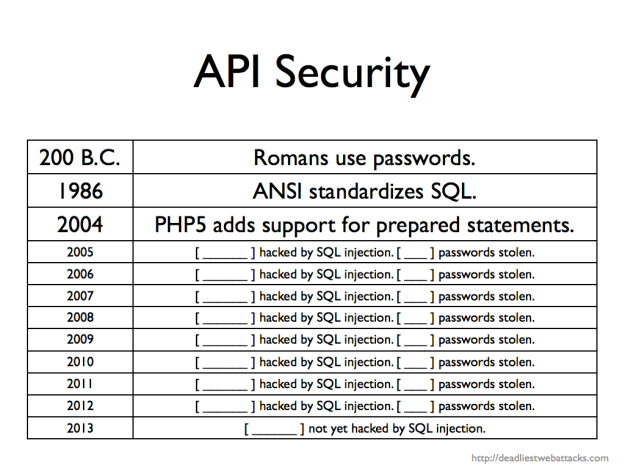

In that presentation I riffed off several topics repeated throughout this site. One topic was the mass hysteria we are forced to suffer from web sites that refuse to write safe SQL statements.

Those of you who are developers may already be familiar with a SQL-related API, though some may not be aware that the acronym stands for Advanced Persistent Ignorance.

Here’s a slide I used in the presentation (slide 13 of 29). Since I didn’t have enough time to complete nine years of research I left blanks for the audience to fill in.

Now you can fill in the last line. Security company Bit9 admitted last week to a compromise that was led by a SQL injection exploit. Sigh. The good news was that no massive database of usernames and passwords (hashed or not) went walkabout. The bad news was that attackers were able to digitally sign malware with a stolen Bit9 code-signing certificates.

I don’t know what I’ll add as a fill-in-the-blank for 2014. Maybe an entry for NoSQL. After all, developers love to reuse an API. String concatenation in JavaScript is no better that doing the same for SQL.

If we can’t learn from PHP’s history in this millennium, perhaps we can look further back for more fundamental lessons. The Greek historian Polybius noted how Romans protected passwords (watchwords) in his work, Histories1:

To secure the passing round of the watchword for the night the following course is followed. One man is selected from the tenth maniple, which, in the case both of cavalry and infantry, is quartered at the ends of the road between the tents; this man is relieved from guard-duty and appears each day about sunset at the tent of the Tribune on duty, takes the tessera or wooden tablet on which the watchword is inscribed, and returns to his own maniple and delivers the wooden tablet and watchword in the presence of witnesses to the chief officer of the maniple next his own; he in the same way to the officer of the next, and so on, until it arrives at the first maniple stationed next the Tribunes. These men are obliged to deliver the tablet (tessera) to the Tribunes before dark.

More importantly, the Romans included a consequence for violating the security of this process:

If they are all handed in, the Tribune knows that the watchword has been delivered to all, and has passed through all the ranks back to his hands: but if any one is missing, he at once investigates the matter; for he knows by the marks on the tablets from which division of the army the tablet has not appeared; and the man who is discovered to be responsible for its non-appearance is visited with condign punishment.

We truly need a fitting penalty for SQL injection vulnerabilities; perhaps only tempered by the judicious use of salted, hashed passwords.

-

Polybius, Histories, trans. Evelyn S. Shuckburgh (London, New York: Macmillan, 1889), Perseus Digital Library. https://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0543.tlg001.perseus-eng1:6.34 (accessed March 5, 2013). ↩

• • • -